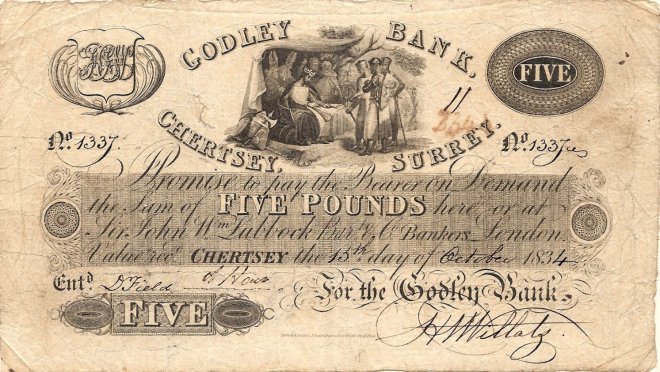

Very few of us question the slips of green paper that come and go in our wallets. Yet confidence in those green slips of paper is a recent phenomenon. As we know, prior to the Civil War, the United States did not have a single national currency. Instead, countless banks issued “bank notes” in a bewildering variety of denominations and designs—more than ten thousand different kinds by 1860. Counterfeiters flourished amid this anarchy, putting vast quantities of bogus bills into circulation.

In the prologue of “A Nation of Counterfeiters” Stephen Mihm discusses the “confidence” and value that users put into the banknotes in the 1800’s (even if they were counterfeit) writing “value was something that was something materialized and became tangible when the note was exchanged, when one person put confidence in the note of another. Only then, at that instant, would an intrinsically worthless piece of paper come to mean something more” (Mihm, 10). In this specific part of the prologue, I feel that Mihm’s outlook on “value” mirrors Georg Simmel’s. Simmel believed that value was not the property of the object, but it is the relation it had with people and other objects. I feel that Mihm mirrors this outlook because he wrote that the “worthless” piece of paper came to mean something when the person receiving the bank note gave it the value they believed it held. So, to one person, the bank note could have been worth a quarter of it’s face value, and to another it could be worth the full face value.

Another interesting part of the prologue that caught my attention was when Mihm briefly talked about credit and creditworthiness. During the 1800’s, different forms of payment had been introduced (i.e., personal checks, drafts, book credits, etc.) These types of payments were different because they put the trust of payment on the individual, rather than the bank. As Mihm states, “these instruments worked best at enabling transactions between individuals who already knew each other” (Mihm, 11). Another book/person who really digs into the meaning of credit and it’s meaning is David Graeber, author of “Debt: The First 5,000 Years.” If you lived in the 1800’s and knew the person you had to pay, you would most likely use personal checks. If the person was a stranger, you would most likely use banknotes. This is because back then, credit was TRUST. Money/banknotes was/is simply an IOU that facilitates trust. This is a statement that Mihm may agree with writing “…bank notes, which put the ‘capital’ in capitalism, were nothing more than glorified IOUs” (Mihm, 9).

Now that we’re adults, and most of us have our first credit cards, we have to learn about the risks that come with credit. Personally, I do not have a credit card and (if I could) would like to keep it that way for the rest of my life. Credit has become a very dangerous asset in everyday life. Credit used to be simple but now it requires so much more. Now there are credit scores and if you don’t have a high enough credit score you can’t get an apartment and in some states, a job. Back then credit used to be essential and positive, but now it only seems to hurt people. How would you describe what credit was (1800’s) and is (now) in our society? Knowing that credit used to be helpful, how did it help create communities in the 1800’s? But how does it hurt communities now?

All in all, I found the prologue of “A Nation of Counterfeiters” by Stephen Mihm to be very interesting. I enjoyed learning that back then, people did not trust the money in circulation and now-a-days we trust the “slips of green paper” without question. But should we? Should we question the dollars that we have in our wallets, purses and pockets? I mean when you think about it, what is the real value of the dollar if there is nothing backing it up? How does the Federal Reserve determine the value? I know, too many questions (this is a topic I shan’t get into because I will go on and on and on and also because it deserves it’s very own blog post) but it would be very interesting to hear all of your guys’ thoughts on everything.

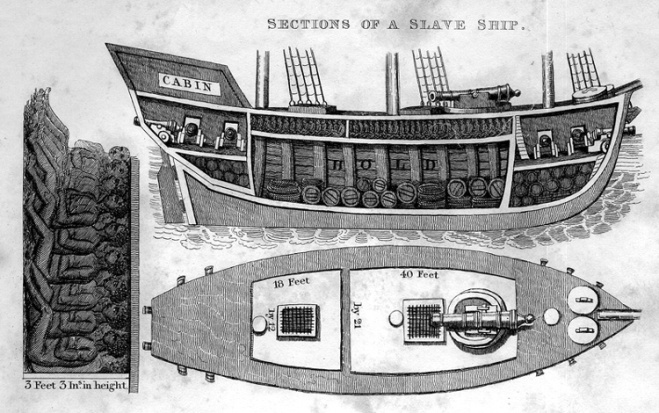

In the article Underground on the High Seas and by Craig B. Hollander talks about the illegal slave trade across the Atlantic. It talks about the people who started it and were the most successful in the business. Two of the most successful illegal slave traders were George Stark and Thomas Sheppard.

In the article Underground on the High Seas and by Craig B. Hollander talks about the illegal slave trade across the Atlantic. It talks about the people who started it and were the most successful in the business. Two of the most successful illegal slave traders were George Stark and Thomas Sheppard.

All historians can agree that the United States’s economy developed into a capitalist powerhouse over the course of the nineteenth century. It grew from a small agrarian economy in 1800 to one of the largest industrial capitalist ones in the world by 1900. But how exactly did this transformation occur? For much of the twentieth century, historians viewed slavery as an obstacle that stood in the path of “true” capitalist development, which was powered by “free” wage labor. This interpretation depicted slavery as inefficient, anomalous, and regionally isolated to the South. How does recent historical scholarship challenge this interpretation, according to historian Seth Rockman in his essay, “The Unfree Origins of American Capitalism”? And if slavery was so integral to the economic success of the United States–as Rockman argues–should anything be done to compensate the descendants of slaves for their ancestors unremunerated work? In answering the last question, it might be helpful to skim journalist Ta-Nahesi Coates’s 2014 essay,

All historians can agree that the United States’s economy developed into a capitalist powerhouse over the course of the nineteenth century. It grew from a small agrarian economy in 1800 to one of the largest industrial capitalist ones in the world by 1900. But how exactly did this transformation occur? For much of the twentieth century, historians viewed slavery as an obstacle that stood in the path of “true” capitalist development, which was powered by “free” wage labor. This interpretation depicted slavery as inefficient, anomalous, and regionally isolated to the South. How does recent historical scholarship challenge this interpretation, according to historian Seth Rockman in his essay, “The Unfree Origins of American Capitalism”? And if slavery was so integral to the economic success of the United States–as Rockman argues–should anything be done to compensate the descendants of slaves for their ancestors unremunerated work? In answering the last question, it might be helpful to skim journalist Ta-Nahesi Coates’s 2014 essay,